We have ideas we use for thinking, and we have ideas we think about.

We are normally only aware of the thoughts we think about. When someone asks us what our philosophy is, these are what we list. They are the objective content of our thinking.

But the ideas we use for thinking are far more consequential. It is with these ideas that we select what we think about, determine what makes sense and is true, relate the ideas we decide to integrate, and build out our sense of objective truth.

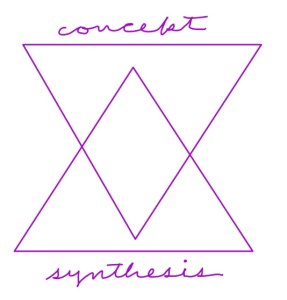

Let us call the ideas we think about and consider important and fundamental our “foreground philosophy”, and those ideas with which we think our foreground philosophy our “background philosophy”.

Most of us barely consider our background philosophy and focus exclusively on the foreground. We manipulate ideas, try out different ways to assemble and disassemble them and generally take our background philosophy as given.

Those who are aware of a background philosophy assume that our foreground philosophies in some way faithfully represent it, and don’t give the matter further thought. To think out the foreground philosophy is to bring one’s background philosophy to light, or bring it to the surface in the manner of depth psychology.

Very few of us suspect that a foreground philosophy differ drastically from its background philosophy, serving as a decoy or diversion, or as an attack-and-defense system to protect and preserve the background.

If we do become curious and venture to reflect on the background, we often make the mistake of the mirror-gazer who, seeing their own eye in the mirror, believes they now see how seeing happens. The foreground philosophy can see itself in the foreground, and believes it has looked into its background.

*

If we do manage to think ideas that affect our background philosophy it is a very different experience from playing with foreground philosophy ideas. It is perplexing and intensely uncomfortable.

It isn’t for everyone.

The stakes feel much higher than they do when playing with foreground philosophy.

For some it no longer feels like play. The consequences are too significant.

But for others, the high-stakes game of background philosophy is the only game consequential enough to inspire their full engagement.

*

Two passages from Nietzsche:

1.

In the writings of a hermit one always hears something of the echo of the wilderness, something of the murmuring tones and timid vigilance of solitude; in his strongest words, even in his cry itself, there sounds a new and more dangerous kind of silence, of concealment. He who has sat day and night, from year’s end to year’s end, alone with his soul in familiar discord and discourse, he who has become a cave-bear, or a treasure-seeker, or a treasure-guardian and dragon in his cave — it may be a labyrinth, but can also be a gold-mine — his ideas themselves eventually acquire a twilight-colour of their own, and an odor, as much of the depth as of the mold, something uncommunicative and repulsive, which blows chilly upon every passerby. The recluse does not believe that a philosopher — supposing that a philosopher has always in the first place been a recluse — ever expressed his actual and ultimate opinions in books: are not books written precisely to hide what is in us? — indeed, he will doubt whether a philosopher can have “ultimate and actual” opinions at all; whether behind every cave in him there is not, and must necessarily be, a still deeper cave: an ampler, stranger, richer world beyond the surface, an abyss behind every ground, beneath every “foundation”. Every philosophy is a foreground philosophy — this is a recluse’s verdict: “There is something arbitrary in the fact that he {the philosopher} came to a stand here, took a retrospect, and looked around; that he here laid his spade aside and did not dig any deeper — there is also something suspicious in it.” Every philosophy also conceals a philosophy; every opinion is also a lurking-place, every word is also a mask.

2.

The dangers for a philosopher’s development are indeed so manifold today that one may doubt whether this fruit can still ripen at all. The scope and the tower-building of the sciences has grown to be enormous, and with this also the probability that the philosopher grows weary while still learning or allows himself to be detained somewhere to become a “specialist” — so he never attains his proper level, the height for a comprehensive look, for looking around, for looking down. Or he attains it too late, when his best time and strength are spent — or impaired, coarsened, degenerated, so his view, his overall judgment does not mean much any more. It may be precisely the sensitivity of his intellectual conscience that leads him to delay somewhere along the way and to be late: he is afraid of the seduction to become a dilettante, a millipede, an insect with a thousand antennae {zum Tausendfuss und Tausend-Fuhlhorn}, he knows too well that whoever has lost his self-respect cannot command or lead in the realm of knowledge — unless he would like to become a great actor, a philosophical Cagliostro {Count Alessandro di Cagliostro (born Giuseppe Balsamo 1743-95): Italian alchemist and adventurer} and pied piper, in short, a seducer. This is in the end a question of taste, even if it were not a question of conscience. Add to this, by way of once more doubling the difficulties for a philosopher, that he demands of himself a judgment, a Yes or No, not about the sciences but about life and the values of life — that he is reluctant to come to believe that he has a right, or even a duty, to such a judgment, and must seek his way to this right and faith only from the most comprehensive — perhaps most disturbing and destructive — experiences, and frequently hesitates, doubts, and lapses into silence. Indeed, the crowd has for a long time misjudged and mistaken the philosopher, whether for a scientific man and ideal scholar or for a religiously elevated, desensualized, “desecularized” enthusiast and sot of God. And if a man is praised today for living “wisely” or “as a philosopher,” it hardly means more than “prudently and apart.” Wisdom — seems to the rabble a kind of escape, a means and a trick for getting well out of a wicked game. But the genuine philosopher — as it seems to us, my friends? — lives “unphilosophically” and “unwisely,” above all imprudently, and feels the burden and the duty of a hundred attempts and temptations of life — he risks himself constantly, he plays the rough game…