Emmanuel Levinas gave me the perfect distinction, totality and infinity, in whose tension religious life flourishes, dies or kills.

All posts by anomalogue

Teaching 11

Martin Heidegger taught me the difference between an emotion and a mood — that is, the difference between a feeling toward an object versus a feeling of a totality — and, in particular, that mood called anxiety which is the feeling of nullified totality, a mood toward subjective nothingness — which Heidegger associated with death, but which I see as the mortal response to infinity in any its myriad forms.

Teaching 10

Eric Voegelin showed me an image of time, of past and future dropping away into inexperienceable darkness in two directions, and gave me my first clear understanding of metaphysics (to which I have added dimensions of space and awareness in my own model of metaphysical situatedness in my spark symbol in the pamphlet I’m preparing to get printed).

Teaching 9

Clifford Geertz helped me see that understanding (or, empathy) is not an act of directly experiencing what another person experiences (which renders understanding impossible, if not essentially absurd), but rather the ability to participate in their symbol system, so that we can understand a proverb, a poem or a joke — or, as I like to add, design something for them that they love with head, hand and heart.

Teaching 8

Ludwig Wittgenstein gave me my best conception of philosophy when he said “the structure of a philosophical problem is ‘here I do not know how to move around.’”

Teaching 7

Richard J. Bernstein taught me how to think about and talk about philosophical experience and to see it everywhere, including in scientific activity and in design.

Teaching 6

Frithjof Schuon taught me that infinity is not an infinite quantity, and, in fact, is not a quantitative concept at all.

Teaching 5

Friedrich Nietzsche taught me that interrogating my own beloved root moral assumptions beyond the limits of permissible questions can transfigure life in unimaginable ways.

Teaching 4

Bruno Latour taught me that material realities are also transcendent, and that they, like all other realities, are immanent in interaction, most of all in resistance to interaction.

Teaching 3

Chantal Mouffe taught me the concept of agonism: that conflict among adversaries is an essential feature of liberal democratic life, and that the attempt to suppress such conflict and to treat our adversaries as enemies is the root of illiberalism.

Teaching 2

Martin Buber taught me that every person is a potential encounter with God if we are willing to relate to the other as a unique, surprising Thou (what he calls the I-Thou relationship), as opposed to an “it.”

Teaching 1

Richard Rorty taught me that progress can be assessed in terms of distance away from negative goals, even when we are unclear of ultimate positive goals we are trying to progress toward.

Book

I’ve contacted some letterpress printers about making my pamphlet, which used to be titled The 10,000 Everythings, but has been sobered up into Geometric Meditations, which is a more precise description of how I use the content of the book.

One printer has responded so far, and suggested some changes that seems to have improved it. I looked at the book again this morning, and I am still happy with it, so it must really be ready. There is only one word in the book that I’m not sure about.

I am producing it as a chapbook, sewn together with red thread, signifying both Ariadne’s thread as well as the Kabbalistic custom of typing a red thread around one’s left wrist to protect from the evil eye. Both are intensely relevant to this project. I have to remember how much I use these diagrams to generate understandings and to keep myself oriented. It is the red thread that connects all my thoughts. So the utility and value of the ideas is beyond doubt. It is true that the form does look and sound somewhat pompous, but it is the best (prettiest and most durable) form for these concepts, so I have to ignore my anxiety about scorn and ridicule from folks who know too little or two much (a.k.a. “evil eye”). At least one angle of understanding yields value, and hermeneutical decency requires that it be read from that angle.

I am incredibly nervous about putting this book out there. I am guessing I’ll just box all the copies up and hide them with my Tend the Root posters.

“Transgressive realism”

Reading the introduction of Jean Wahl’s Human Existence and Transcendence, I came across this:

With this critique, Jean Wahl, at least I would argue, anticipates an important dimension of contemporary Continental thought, which has recently been quite daringly called by an anglo- saxon observer, “transgressive realism”: that our contact with reality at its most real dissolves our preconceived categories and gives itself on its own terms, that truth as novelty is not only possible, though understood as such only ex post facto, but is in fact the most valuable and even paradigmatic kind of truth, defining our human experience. The fundamental realities determinative of human experience and hence philosophical questioning — the face of the other, the idol, the icon, the flesh, the event… and also divine revelation, freedom, life, love, evil, and so forth — exceed the horizon of transcending- immanence and give more than what it, on its own terms, allows, thereby exposing that its own conditions are not found in itself and opening from there onto more essential terrain.

“Transgressive realism” jumped out at me as the perfect term for a crucially important idea that I’ve never seen named. I followed the footnote to the paper, Lee Braver’s “A brief history of continental realism” and hit pay dirt. Returning to Wahl, I find myself reading through Braver’s framework, which, of course, is a sign of a well-designed concept.

Braver presents three views of realism, 1) Active Subject (knowledge is made out out of our own human subjective structures, and attempting to purge knowledge of these subjective forms is impossible), 2) Objective Idealism (reality is radically knowable, through a historical process by which reality’s true inner-nature is incorporated into understanding), and 3) Transgressive Realism, which Braver describes as “a middle path between realism and anti-realism which tries to combine their strengths while avoiding their weaknesses. Kierkegaard created the position by merging Hegel’s insistence that we must have some kind of contact with anything we can call real (thus rejecting noumena), with Kant’s belief that reality fundamentally exceeds our understanding; human reason should not be the criterion of the real. The result is the idea that our most vivid encounters with reality come in experiences that shatter our categories…”

Not only is there an outside, as Hegel denies, but we can encounter it, as Kant denies; these encounters are in fact far more important than what we can come up with on our own. The most important ideas are those that genuinely surprise us, not in the superficial sense of discovering which one out of a determinate set of options is correct, as the Kantian model allows, but by violating our most fundamental beliefs and rupturing our basic categories.

This concept is fundamental to my own professional life (studying people in order to re-understand them and the worlds they inhabit, in order induce innovations through perspective shift), to my political ideal (liberalism, the conviction that all people should be treated as real beings and not instances of other people’s categories, because each person packs the potential to disrupt the very categories we use to think them) and my deepest religious convictions (the most reliable door to God is through the surprising things other people can show you and teach you, which can shock and transfigure us and our worlds.)

Though I am Jewish — no, because I am Jewish — I will never stop admiring Jesus for combining into a single commandment the Ve’ahavta (“and you will love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul and with all your strength”) with the imperative to love your neighbor as yourself. Incredible!

Press

I want to start a press which publishes individual short philosophical and theological essays written in the magisterial mode. The purpose is to give thinkers permission to make straightforward, beautiful presentations of their own ideas unencumbered by concerns unrelated to communication of ideas.

The typesetting, printing and binding of these essays will be the highest quality. Authors should fear being upstaged by the design.

Guidelines for publication:

- Material connects with experiences outside the confines of academic life.

- Technical terms are used as sparingly as possible and defined within the essay.

- No footnotes, endnotes, citations, or any kind of direct references to other works in the body of the text are permitted (though unobtrusive allusions that subtly nod to sources without depending on them to carry the meaning of the thought are allowed, or at least will not be aggressively excluded).

- Language is optimized for elegance at the expense of thoroughness, defensibility and etiquette.

I need a name for this press.

Paradox of distance

The closer you get, the more perceptible the remaining distance becomes.

*

Flaws intensify as perfection is approached.

*

Narrow disparities gall worse than vast ones.

*

When a power gap narrows, two things happen: 1) The remaining gap infuriates us as it diminishes and 2) the narrowness of the gap tempts us to take our chances and turn the tables.

Divine trigger

Other minds are our most accessible source of divine alterity, of the accessibly alien, but for this very reason our most intrusive source of dread.

The accessibly alien is a thin dark ring of potential-understanding separating the bright spark of understanding from the infinite expanse of blindness beyond understanding, which some people call “absurd”, others call “mystery”, and others call “nothing”.

As long as we discuss common objects, the things standing around us illuminated by our common understandings. we seem alike. We come from the same place, we want similar things, and we live together peacefully as neighbors.

But when we try to share what is nearest to us with our nearest neighbor the divine alterity shows. As distance diminishes, our innerness — the source of illumination that gives our knowledge meaning — burns with intolerable blinding intensity, and the light it radiates turns strange, hinting in a way that cannot be doubted how much deeper, wider, denser, inexhaustible and incomprehensible reality is, and how thin and partial even the most thorough knowledge is. Too much is exposed. Perplexity engulfs us, and anxiety floods in.

Our stomachs drop, our chests tighten and burn, acid rises in the backs of our throats. Our alarms go off, and the talk will be made to stop. Only the most trusting love and disciplined faith will pull us across the estrangement. This is what it takes to raise two divine sparks.

To many of us this dread seems a mortal threat. And we are right in a sense.

Transcendence, love and offense

Transcendence is what gives all things authentic value, positive and negative.

Positively, when we value anything, and especially when we love someone, what we authentically value is precisely the reality beyond the “given”, that is, beyond what we think and what we immediately experience.

If we only love the idea of someone or if we only love the experience of being with someone, while rejecting whatever of them (or more accurately “whoever of them”) defies our will, surprises our comprehension, breaks our categorical schemas and evades our experience, we value only what is immanent to our selves: an inner refraction of self that has little to do with the real entity valued. To authentically value , to love, we must must want most of all precisely what is defiant, surprising, perplexing and hidden.

To want only what we can hope to possess is to lust; to be content with what we have is to merely like, and no amount or intensity of lusting or liking adds up to love. (To put it in Newspeak, love is not double-plus-like. Love is not the extreme point on the liking continuum, but something qualitatively and, in truth, infinitely different.)

Conversely, authentic negative value — authentic offense — is our natural and spontaneous response when another person interacts with us as if we are essentially no more than what we are to them. They reduce us without remainder to what they believe us to be, and to how they experience us. In doing this, they deny our transcendent reality. This is the universal essence of offense.

When a social order is roughly equal, it is difficult, if not impossible, for one person to oppress another with such treatment. A person can either shun the would-be oppressor, or make their reality felt by speaking out or refusing to comply with expectations. But in conditions of inequality, threat or dependence can compel a person to perform the part of the self a more powerful person imagines. This is where offense gives over to warranted hostility.

The fashionable conventional wisdom, which has been drilled into the heads of the young, gets it all backwards. Ask the average casually passionate progressivist what is wrong with racism or sexism you’ll get an answer to the effect of “racism and sexism produce or reinforce inequality and oppression.” But the truth of the matter is that inequality is bad because it allows people to get away with forcing other people to tolerate, if not actively self-suppress, self-deny and perform the role the powerful demand of them. And part of that performance is asserting the truth the powerful impose.

“Pascal’s Sphere” by Jorges Luis Borges

(Published in multiple collections, including Labyrinths and Other Inquisitions.)

Perhaps universal history is the history of a few metaphors. I should like to sketch one chapter of that history.

Six centuries before the Christian era Xenophanes of Colophon, the rhapsodist, weary of the Homeric verses he recited from city to city, attacked the poets who attributed anthropomorphic traits to the gods; the substitute he proposed to the Greeks was a single God: an eternal sphere. In Plato’s Timaeus we read that the sphere is the most perfect and most uniform shape, because all points on its surface are equidistant from the center. Olof Gigon (Ursprung der griechischen Philosophie, 183) says that Xenophanes shared that belief; the God was spheroid, because that form was the best, or the least bad, to serve as a representation of the divinity. Forty years later, Parmenides of Elea repeated the image (“Being is like the mass of a well-rounded sphere, whose force is constant from the center in any direction”). Calogero and Mondolfo believe that he envisioned an infinite, or infinitely growing sphere, and that those words have a dynamic meaning (Albertelli, Gli Eleati, 148). Parmenides taught in Italy; a few years after he died, the Sicilian Empedocles of Agrigentum plotted a laborious cosmogony, in one section of which the particles of earth, air, fire, and water compose an endless sphere, “the round Sphairos, which rejoices in its circular solitude.”

Universal history followed its course. The too-human gods attacked by Xenophanes were reduced to poetic fictions or to demons, but it was said that one god, Hermes Trismegistus, had dictated a variously estimated number of books (42, according to Clement of Alexandria; 20,000, according to Iamblichus; 36,525, according to the priests of Thoth, who is also Hermes), on whose pages all things were written. [Anomalogue: From what I’ve read, Hermes Trismegistus was not a god; the god Hermes is a different being.] Fragments of that illusory library, compiled or forged since the third century, form the so-called Hermetica. In one part of the Asclepius, which was also attributed to Trismegistus, the twelfth-century French theologian, Alain de Lille — Alanus de Insulis — discovered this formula which future generations would not forget: “God is an intelligible sphere, whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” The Pre-Socratics spoke of an endless sphere; Albertelli (like Aristotle before him) thinks that such a statement is a contradictio in adjecto, because the subject and predicate negate each other. Possibly so, but the formula of the Hermetic books almost entitles us to envisage that sphere. In the thirteenth century the image it reappeared in the symbolic Roman de la Rose, which attributed it to Plato, and in the Speculum Triplex encyclopedia. In the sixteenth century the last chapter of the last book of Pantagruel referred to “that intellectual sphere, whose center is everywhere and whose circumference nowhere, which we call God.” For the medieval mind, the meaning was clear: God is in each one of his creatures, but is not limited by any one of them. “Behold, the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain thee,” said Solomon (I Kings 8:27). The geometrical metaphor of the sphere must have seemed like a gloss of those words.

Dante’s poem has preserved Ptolemaic astronomy, which ruled men’s imaginations for fourteen hundred years. The earth is the center of the universe. It is an immovable sphere, around which nine concentric spheres revolve. The first seven are the planetary heavens (the heavens of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn); the eighth, the Heaven of Fixed Stars; the ninth, the Crystalline Heaven (called the Primum Mobile), surrounded by the Empyrean, which is made of light. That whole laborious array of hollow, transparent, and revolving spheres (one system required fifty-five) had come to be a mental necessity. De hypothesibus motuum coelestium commentariolus was the timid title that Copernicus, the disputer of Aristotle, gave to the manuscript that transformed our vision of the cosmos. For one man, Giordano Bruno, the breaking of the sidereal vaults was a liberation. In La cena de le ceneri he proclaimed that the world was the infinite effect of an infinite cause and that the divinity was near, “because it is in us even more than we ourselves are in us.” He searched for the words that would explain Copernican space to mankind, and on one famous page he wrote: “We can state with certainty that the universe is all center, or that the center of the universe is everywhere and the circumference nowhere” (De la causa, principio e uno, V).

That was written exultantly in 1584, still in the light of the Renaissance; seventy years later not one spark of that fervor remained and men felt lost in time and space. In time, because if the future and the past are infinite, there will not really be a when; in space, because if every being is equidistant from the infinite and the infinitesimal, there will not be a where. No one exists on a certain day, in a certain place; no one knows the size of his face. In the Renaissance humanity thought it had reached adulthood, and it said as much through the mouths of Bruno, Campanella, and Bacon. In the seventeenth century humanity was intimidated by a feeling of old age; to vindicate itself it exhumed the belief of a slow and fatal degeneration of all creatures because of Adam’s sin. (In Genesis 5:27 we read that “all the days of Methuselah were nine hundred sixty and nine years”; in 6:4, that “There were giants in the earth in those days.”) The elegy Anatomy of the World, by John Donne, deplored the very brief lives and the slight stature of contemporary men, who could be likened to fairies and dwarfs. According to Johnson’s biography, Milton feared that an epic genre had become impossible on earth. Glanvill thought that Adam, God’s medal, enjoyed a telescopic and microscopic vision. Robert South wrote, in famous words, that an Aristotle was merely the wreckage of Adam, and Athens, the rudiments of Paradise. In that jaded century the absolute space that inspired the hexameters of Lucretius, the absolute space that had been a liberation for Bruno, was a labyrinth and an abyss for Pascal. He hated the universe, and yearned to adore God. But God was less real to him than the hated universe. He was sorry that the firmament could not speak; he compared our lives to those of shipwrecked men on a desert island. He felt the incessant weight of the physical world; he felt confused, afraid, and alone; and he expressed his feelings like this: “It [nature] is an infinite sphere, the center of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere.” That is the text of the Brunschvicg edition, but the critical edition of Tourneur (Paris, 1941), which reproduces the cancellations and the hesitations of the manuscript, reveals that Pascal started to write effroyable: “A frightful sphere, the center of which is everywhere, and the circumference nowhere.”

Perhaps universal history is the history of the diverse intonation of a few metaphors.

- Buenos Aires, 1951

Ambiliberalism report, late 2019

This weekend I hit a political breaking point. While my political position is as liberal as ever, and in better times would be considered left-of-center, Progressivism has become so dominant in left-wing politics and as a whole has drifted so far from liberalism I have realized it no longer makes sense to emphasize my points of agreement with it. I am now entirely and openly opposed to it, not only to its methods and rhetoric, but to its ideal.

Progressivism presents itself as anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-prejudice, but does so by redefining racism, sexism and “bad” prejudice as bad only when deployed from positions of power. This means that if you claim to speak on behalf of a less powerful identity you can indulge your hatred toward (allegedly) more powerful categories of people without the risk of being called a racist, a sexist, or a bigot and whatever hateful language you use or vicious sentiments you express cannot be called hate speech, because you are “punching up” from a position of relative weakness.

And because Progressivists have a monopoly on determining what identities are politically relevant and which are not, Progressivism is protected from being itself understood as an identity — much less an overwhelmingly powerful identity. In many social milieus, including corporate workplaces, Progressivism is by far the most powerful ideology, both capable and eager to “punch down” with crushing force from positions of authority.

Progressivists have a collective habit of scoffing at such claims and reacting in the manner that all overwhelmingly powerful groups do when confronted with their own prejudice (with dismissal, fragility, offense, rage, etc.). They appear to lack the ironic and emotional self-discipline to recognize when they themselves are facing truths outside their own comfort zones and to respond with the empathy and openness they demand from others.

So, I’m not even sure what the practical consequence this shift will have besides refusing to stress points of agreement when speaking with Progressivists, and not pleading with them to see me as a fellow left-liberal. They’re not liberals, and I’m not all that sure most of them know what left means, either. I’m definitely not going to cooperate with racist, sexist, bigoted and hate-saturated redefinitions of racism, sexism, bigotry and hate speech. They need to be called out, however unpopular they are and however much racists and sexists and bigots resent being told the truth.

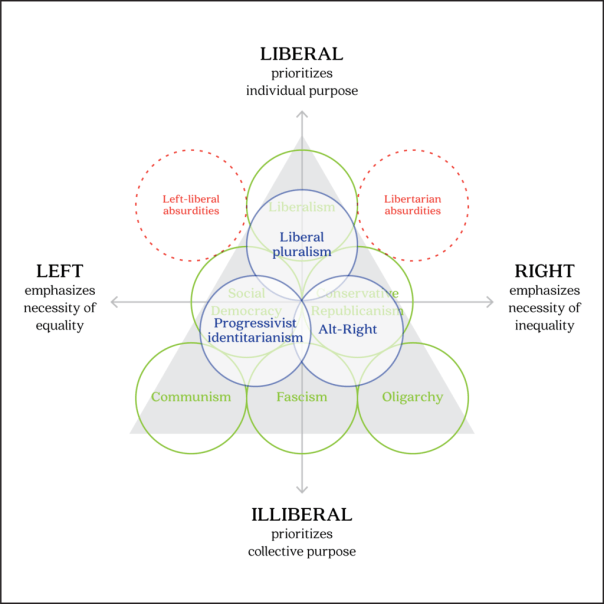

I’ve also redrawn my Ambiliberal diagram to situate my own Liberal Pluralism against Progressivist identitarianism and its antithetical twin, the Alt-Right.