I’m thinking out loud here, so please forgive the tedium and unclarity. I’m also traveling, and that always messes me up pretty seriously. Just to get these thoughts out, I’m saying what comes to mind and not worrying excessively over how much sense I’m making much less how persuasive I’m being. So there’s even less reason to read this post than there usually is, so I encourage my nonexistent readership to ignore this post with redoubled nonawareness of its existence.

I just finished Ricoeur’s essay “The Problem of Double Meaning” from Conflict of Interpretations and this is my attempt to digest the material. Here is (in slightly streamlined form) the conclusion of the essay:

It seems to me that the conquest of this deliberately and radically analytic level allows us to better understand the relations between the three strategic levels which we have successively occupied. We worked first as exegetes with vast units of discourse, with texts, then as lexical semanticians with the meaning of words, i.e., with names, and then as structural semanticians with semic constellations. Our change of level has not been in vain; it marks an increase in rigor and, if I may say so, in scientific method. … It would be false to say that we have eliminated symbolism; rather, it has ceased to be an enigma, a fascinating and possibly mystifying reality, to the extent that it invites a twofold explanation. It is first of all situated in relation to multiple meaning, which is a question of lexemes and thus of language. In this respect, symbolism in itself possesses nothing remarkable; all words used in ordinary language have more than one meaning. … Thus the illusion that the symbol must be an enigma at the level of words vanishes; instead, the possibility of symbolism is rooted in a function common to all words, in a universal function of language, namely, the ability of lexemes to develop contextual variations. But symbolism is related to discourse in another way as well: it is in discourse and nowhere else that equivocalness exists. Discourse thus constitutes a particular meaning effect: planned ambiguity is the work of certain contexts and, we can now say, of texts, which construct a certain isotopy in order to suggest another isotopy. The transfer of meaning, the metaphor (in the etymological sense of the word), appears again, but this time as a change of isotopy, as the play of multiple, concurrent, superimposed isotopies. [See comment 1 below] The notion of isotopy has thus allowed us to assign the place of metaphor in language with greater precision than (lid the notion of the axis of substitutions…

But then, I ask you, does the philosopher not find his stake in the question at the end of this journey? Can he not legitimately ask why in certain cases discourse cultivates ambiguity? The philosopher’s question can be made more precise: ambiguity, to do what? Or rather, to say what? [See comment 2 below] We are brought back to the essential point here: the closed state of the linguistic universe. To the extent that we delved into the density of language, moved away from its level of manifestation, and progressed toward sublexical units of meaning — to this very extent we realized the closed state of language. [See comment 3 below] The units of meaning elicited by structural analysis signify nothing; they are only combinatory possibilities. They say nothing; they conjoin and disjoin.

There are, then, two ways of accounting for symbolism: by means of what constitutes it and by means of what it attempts to say. What constitutes it demands a structural analysis, and this structural analysis dissipates the “marvel” of symbolism. That is its function and, I would venture to say, its mission; symbolism works with the resources of all language, which in themselves have no mystery.

As for what symbolism attempts to say, this cannot be taught by a structural linguistics; in the coming and going between analysis and synthesis, the going is not the same as the coming. On the return path a problematic emerges which analysis has progressively eliminated. Ruyer has termed it “expressivity,” not in the sense of expressing emotion, that is, in the sense in which the speaker expresses himself, but in the sense in which language expresses something, says something. The emergence of expressivity is conveyed by the heterogeneity between the level of discourse, or level of manifestation, and the level of language, or level of immanence, which alone is accessible to analysis. Lexemes do not exist only for the analysis of semic constellations but also for the synthesis of units of meaning which are understood immediately. [See comment 4 below]

It is perhaps the emergence of expressivity which constitutes the marvel of language. Greimas puts it very well: “There is perhaps a mystery of language, and this is a question for philosophy; there is no mystery in language.” [See comment 5 below.] I think we too can say that there is no mystery in language; the most poetic, the most “sacred,” symbolism works with the same semic variables as the most banal word in the dictionary. But there is a mystery of language, namely, that language speaks, says something, says something about being. If there is an enigma of symbolism, it resides wholly on the level of manifestation, where the equivocalness of being is spoken in the equivocalness of discourse.

Is not philosophy’s task then to ceaselessly reopen, toward the being which is expressed, this discourse which linguistics, due to its method, never ceases to confine within the closed universe of signs and within the purely internal play of their mutual relations?

*

COMMENTS:

- This accounts for why many Nietzsche scholars miss Nietzsche’s most interesting philosophizing. They discover a single isotopy, which works at the sea-level level of explicit assertions, and they fail to notice the layers of isotopy beneath the argumentation, despite numerous explicit assertions that these levels do exist and ought to be sought.

- This is a fascinating question, and it connects directly with why I began to study hermeneutics. I didn’t know how to think about the kind of truth experienced through understanding of symbols.

The understanding of symbolic works depends entirely on a reader’s ability to recognize in a symbolic form an analogous form which is indicated obliquely. The reasons for oblique indication are numerous, but the most compelling reason is sheer impossibility of direct expression, which means they refer to what we call radically subjective experience. The subjective experiences I’ve encountered are sometimes unprecedented emotional states, a sense of concealed possibility, novel intellectual “moves” (dance imagery is frequently used), and metaphysical noumena of various kinds (which I am reducing to “experiences of”, or what a friend of mine calls “exophany”, but in the spirit of phenomenological method, which means to defy reductionism: I find disbelief and comprehension of metaphysical reality equally impossible.).

The effectiveness of radically subjective symbols presupposes the existence of subjective experiences the symbols indicate. A peculiarity of many of these experiences is their utter ephemerality. It appears they are remembered very differently from objective facts, over which we have a higher degree of command, and therefore can prefer to such a degree that we wish to deny the existence of anything but objectivity. A fact or image can be summoned from memory at will like a servant who is normally obedient. But a mood or insight or spirit has a mind of its own, and must be recalled in an almost petitionary attitude: we recollect images and facts and try to create conditions upon which the experience can (to use Octavo Paz’s word) condense, almost as if they are offerings or a home made hospitable for a guest. I think this is actually the importance of prayer. We recall a forgotten spirit, in the hope we will be inhabited once again, and that once present, we will not be abandoned.

Other double meanings (which I prefer not to call symbols) indicate things that could be very easily expressed in objective language, but which are socially prohibited. The reason “that’s what she said” works so well is because of the legacy of sexual taboo, where all the objects and activities associated with sex were veiled in innuendo. Puns are similar; it is the exercise of the facilities involved in symbolization, but connecting banalities. This is the core problem of very clever people: their activities fail to deliver insights, and are performed only to demonstrate skill.

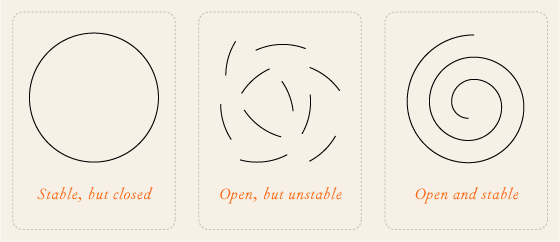

- More and more, this is the difference I see between science and philosophy. Science works within a fixed horizon, analyzing and synthesizing within a framework that is presupposed and not treated as problematic, because it is simply taken as reality itself. This does not only apply to scientific paradigms, but to the metaphysic of science itself which appears in most cases to be entirely innocent. Philosophy, however, concerns itself with the horizons, and attempts to transcend their limits, a process which takes place within the very limits to be transcended.

It is also ethically significant that philosophy attempts to move outside the closed circle of language. More and more, my own conception of evil is bound up with the refusal to acknowledge being beyond one’s own conceptions of reality. One limits reality to that which one is capable of intellectually mastering, which is objective knowledge as framed by one’s own subjective perspective and which excludes the possibility of subjectivities, particularly super-individual forms of subjectivity that threaten to expose individual intellect as an organ of greater scales of intellect, which include at minimum family, culture and language. Evil is rooted in the attempt to make the mind a place of its own, far from that which challenges its absolute sovereignty over its private universe.

- This reminds me a lot of a diagram I used to draw to show the relationship between synthesis and concept. Synthesis means “put together”, and I classify systematization of wholes constituted of atomic elements as a type of synthesis. However, the synthesis reflects another order of reality which is concept, which means “take together”. I think this corresponds to a mememe — an indivisible unit of meaning which is spontaneously grasped as a whole, or gestalt (or to say it in nerd, the whole is “grokked”). It might make sense to see the activity of trying to understand as systematizing and resystematizing parts until they are arranged into a form that is recognized by the intuition as a concept, at which point the understanding occurs. I may need to return to this thought, because it really is relevant to design.

- I suspect the desire to locate mystery in the words themselves rather than in what the words indicate is one more manifestation of preference for objectivity. The words are fetishized as the locus of the mystery, which is a form of idolatry. Idol, after all is derived from the Greek word eidos ‘form, shape.’ The formula: the ground of reality of which we are made entirely, in which we always participate, but which surpasses us and moves us is impossible to think about in objective terms, and for this reason we reduce it to objective terms. To put it in the language of Martin Buber, the ground of reality is related to in terms of I-Thou, but we reduce it to terms of I-It. And other people, with whom we exist in relationship, as part of the ground — we prefer to relate to them also in terms of I-It — for exactly the same reason. We want to elevate ourselves above participatory relationship which involves and changes us, and instead to look at others across an insulating distance that promises to preserve us inert.