To be assigned responsibility for something is almost synonymous with taking care of all the details of some work activity or work product. But rarely is anyone assigned responsibility for maintaining the vision of the whole in the execution of the parts.

A management truism applies: “If nobody is responsible for getting a job done, it won’t get done.”

*

If you suggest that vision needs to be managed apart from the details many people will dismiss the thought on the grounds that once you’ve conceived an idea (in the form of a strategy or a concept), and developed a plan to execute it, the whole is contained in the details.

This is untrue.

It only seems that way because the majority of businesspeople are intellectually blind to wholeness. It isn’t that they can’t feel the difference between a whole and a fragmented mess — it’s just that they don’t know how to think about the problem and prefer to ignore it. We let wholes slide, because it’s hard to bust someone for neglecting a whole. It feels very… subjective. Parts are objective, so that’s where we focus.

But ignoring wholes is what makes so many companies competent but mediocre.

*

Philosophies have practical consequences, even when we are not aware we hold any philosophy at all. As Bob Dylan said: “It might be the devil / or it might be the Lord / but you’ve gotta serve somebody.” Actually, it is especially when we are unaware it that a philosophy’s influence is strongest, determining our thoughts, perceptions and action.

One philosophy 95% of people in the modern world believe without knowing it, which they have unconsciously absorbed through cultural osmosis and accepted unquestioningly, is atomism.

According to atomism, wholes are made entirely out of parts. Once all the parts are accounted for, the whole is accounted for as well. In other words, wholes are reducible to parts.

Holism asserts that wholes have an existence independent of their particular constitution (of parts). Some holists say that wholes are what give meaning to parts, and that parts deprived of the context of a whole are inconceivable. Reductionistic holists go as far as to claim that all we have is wholes which have been artificially or arbitrarily divided up into parts.

I’m against reductionism on principle. I think wholes have one kind of being, and parts have another kind of being, and that human beings find life most satisfying when wholes and parts are made to converge.

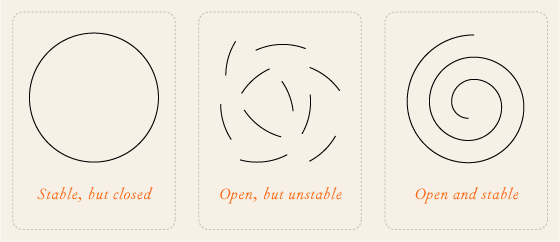

And my philosophy has practical consequences: wholes need management as much as parts do. And when you do not explicitly manage a wholes the parts will overpower, degrade and smother the whole.

This happens to products, to initiatives, and to organizations.

We forget wholes, mostly because we don’t understand what they are and how they work.

*

Inevitably and automatically, if allowed to develop by their own logic, parts diverge from the whole.

Parts tend to work themselves out according to the most local conditions, governed more by expedience, habit and myopia than by the guidance of vision. This type of localized logic is made of very crude forces and very tangible considerations.

Envisaged wholes are more fragile, at least at the beginning, before they are firmly established. They must be protected from the roughness of localized logic, like as we fence off sprouts and saplings until they’ve established themselves and no longer need protection.

Envisaged wholes (especially unprecedented wholes) are vulnerable in three specific ways. They are essentially inchoate, elusive, ephemeral .

- Envisaged wholes are essentially inchoate. — We tend to think of vision as being the envisioning of a whole, a detailed picturing of some possible reality. That is not how it happens. Vision is sensing a possibility. Some of the possibility is given in broad outline, and some of it is given in arbitrary detail, but most of it is simply latent in a situation, there but inaccessible to the imagination. As the situation develops under guidance of the vision, the development is recognized as conforming or deviating from the vision. But what is strange is that the vision itself is affected by the recognition. The vision understands itself, reflected in the concrete attempts to actualize it, in a dialogical process of revelation. This is why visions are not directly translatable into plans. The plan must accommodate and support the development of the vision, or it is only a recipe for sterility.

- Envisaged wholes are elusive. — While virtually all people are capable of recognizing and categorizing objects, and virtually every professional is capable of grasping processes and plans, relatively few are able to understand or conceive concepts, even after they have been clarified and articulated. An envisaged whole gains concreteness, clarity and general accessibility in the course of its development, and as it does it comes into view of more and more people. In its early stages, though, the fact of its existence, much less its nature will be far from obvious, and completely beyond the grasp of most people. Those with firsthand experience with vision know this process. Those who don’t either operate by faith and support the process or they undermine it, or they create conditions where vision doesn’t even happen. (In many organization, the wholes are determined solely by leadership; but leadership is earned through success in managing details. The result: the only people able to earn the right to set vision are precisely the ones with absolutely no awareness of vision. They try to provide their organizations with “vision”, but all they know how to come up with are ambitions, metrics, and plans to accomplish what’s been done before.)

- Envisaged wholes are ephemeral. — Because of how they are known, envisaged wholes are very easily corrupted and forgotten. They are revealed in dialogue with concrete actualization. The vision tries to respond to the actualization. If the actualization is not responsive to the vision and moves away from it far enough, the vision will lose not only its hold on the process, it will get caught up in the localized logic of the development and lose itself altogether. This is what is meant by getting “too close to the situation”. The vision holder must maintain the right balance of contact with the situation — close enough to guide it, but far enough from it to see when the development has begun to go off-track. When nobody is permitted the distance, and everyone is required to roll up their sleeves and get mired in the details, the vision’s chances of survival are nil. The problem is not with the vision, nor with the visionary, but with the absence of conditions necessary for maintaining vision.

*

The captain of a ship, after charting the ship’s course and pointing it in the right direction, went below deck and grabbed an oar.