Any form of participation in a whole experienced solely from within (in which the participant participates as a part) of which we have only partial knowledge is, in itself inconceivable. Withinness topologically thwarts comprehension.

We cannot conceive the whole, but we can conceive the fact that we are participants in it, and we can conceive many characteristics of our participation. For instance, we can conceive things we might do or think or feel in response to our immediate encounter with fellow participants or parts within the whole. We can conceive that the whole exists, that we are situated within it, that it environs us, and we can understand how we participate in that whole as a part of it, even if we do not comprehend the whole in the conceptual way we comprehend objects in our environment or other kinds of things we can wrap our minds around.

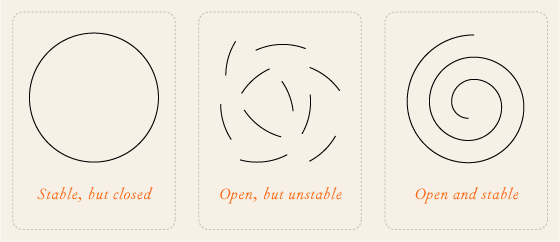

We might even try to map what we are able to conceive from within and try to make what we are within conceivable.

For instance, if we are trapped in a labyrinth, we might draw a maze map that represents, from the outside, the space we are inside, so we can better comprehend it as a whole instead of as a connected series of situations. We transpose the multiple interior positions to a single exterior form. We evert it, and what remains inside now views an exterior representation of its situation and mentally re-situates itself outside.

We might even get so absorbed in the maze that we forgets that it we still located in some space within the labyrinth and not on some dot marked on the maze, in the same way as we forget that our brain is something known by the mind, not the other way around.

*

The first all-consuming perplexity I experienced reading Nietzsche resolved in an image of a mandala.

At the zenith of the mandala was a point I labeled “Solipse”. At the nadir was another point labeled “Eclipse”.

Next to Solipse I wrote “World-in-me” and drew a little circle with a dot at its center, with a caption “Ptolemy”.

Next to Eclipse I wrote “I-in-world” and drew another little circle with a dot on the periphery with a caption “Copernicus”.

In solipse, brains are found inside minds, along with every known thing. In eclipse, minds are produced from brains which exist at points in space.

This was the origin of my topological sense of understanding.

The perpendicular points between solipse and eclipse marked inflections between these two everted ways to situate self and world, moments where both situations become conceivable, perhaps together in ambinity, and for a time neither fully dominates, but co-exist in all-everting multistability.

From these two points we can see most clearly how the inside of an oyster shell is an everted pearl, Pandora’s box is everted Paradise, and Eden is the everted fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

Here we can conceive both ultimate eversions simultaneously. We can use maps without forgetting where that map really is, but also move around in space and allow maps to deepen our understanding of our situation. Our minds are improved with knowledge of brains, but our knowledge of brains is improved knowing that all knowledge is mind-product.

Much later, moving along this wheel, at one of these ambinity points where inside and outside exist within one another, I intuited a beyondness of both, a ground of soliptic-ecliptic eversion that is both and neither. From that point on, I was religious.

*

At the beit din before I went into the mikvah a rabbi interrupted me in the middle of an answer to one of their questions, and asked “Do you even really believe in God?” I said, “Yes; but in a way that is extremely difficult to explain.” She said “Very Jewish. Fair enough.” Fifteen minutes later I emerged from the mikvah a Jew with a new Hebrew name, Nachshon, after the general of the tribe of Judah who, according to legend, waded into the chaotic turbulence of the Red Sea all the way up to his nostrils, just before Moses split the waters into two halves, permitting passage from one shore to the other. Adonai eloheinu; Adonai echad.

*

I need to think carefully how I might use the word “participate” in my topological conceptive vocabulary, which, as I mentioned yesterday, is built around con-capere words.

Participate shares the same root as concept, conception, conceive: capere “take”

part- “part” + –capere “take” – to part-take.

con- “together” + -capere “take” – to together-take.