Have you ever been in a deep, inspired conversion with a friend and noticed that you were waiting with your friend to hear what you would say next? Did the world change for you? Did it wear off?

Have you ever been absorbed in a book and had difficulty adjusting back to the normal world?

Have you ever remembered a happy time and found it impossible to believe you were happy?

Have you ever spoken to a friend and realized they were no longer your friend? By this I do not mean that the person no longer considers you a friend – I mean the one who was your friend no longer exists behind this familiar face speaking in this unfamiliar voice.

…

We have ways of accounting for these experiences. We account for them to one another, and we accept these accounts.

These ways of accounting for experience are not the only ways, however. In past centuries things were understood differently and consequently experienced differently. Even at this moment, experience may be understood and experienced radically differently by the people around you. They share your environment. When they speak they use the same words. They work with you, maybe collaborate closely with you. Nonetheless, they may dwell in a very different world than the one you know.

Perhaps our way of accounting for experience conceals and protects us from the depth of the difference.

=====

OPTIONAL ETYMOLOGICAL PLAY

(Feel free to skip this part.)

*

Subject – ORIGIN Latin subjectus ‘brought under,’ past participle of subicere, from sub– ‘under’ + jacere ‘throw.’ Senses relating to philosophy, logic, and grammar are derived ultimately from Aristotle’s use of to hupokeimenon meaning material from which things are made and subject of attributes and predicates. Hupokeimenon means ‘that which lies underneath’.

Object – ORIGIN medieval Latin objectum ‘thing presented to the mind,’ neuter past participle (used as a noun) of Latin obicere, from ob– ‘toward, against, in the way of’ + jacere ‘to throw’.

*

An interesting fact: In most traditions Heaven is considered masculine, and Earth is considered feminine.

‘Heaven covers, Earth supports’

*

Matter – ORIGIN Middle English : via Old French from Latin materia ‘timber, substance,’ also ‘subject of discourse,’ from mater ‘mother.’

Substance – ORIGIN Latin substantia ‘being, essence,’ from substant– ‘standing firm,’ from the verb substare, sub– ‘under’ + stare ‘to stand.’

Understand?

*

Check this out:

Contrast – ORIGIN Late 17th cent. as a term in fine art, in the sense of juxtapose so as to bring out differences in form and color): from French contraste (noun), contraster (verb), via Italian from medieval Latin contrastare, from Latin contra– ‘against’ + stare ‘stand.’)

*

Try this on:

Subject (throw under) : Object (throw against)

::

Substance (stand under) : Contrast (stand against) ?

*

Creepy, related words:

Succubus – A female demon believed to have sexual intercourse with sleeping men. ORIGIN late Middle English : from medieval Latin succubus ‘prostitute,’ from succubare, from sub– ‘under’ + cubare ‘to lie.’

Incubus – A male demon believed to have sexual intercourse with sleeping women. ORIGIN Middle English : late Latin form of Latin incubo ‘nightmare,’ from incubare ‘lie on’ (see incubate).

*

End of ETYMOLOGICAL PLAY

=====

A person would be blind to his own subjectivity if it weren’t for contrasting subjectivities.

There are two sources of contrasting subjectivity which when taken together, one reveal what subjectivity essentially is: 1) other people; 2) changes to one’s own subjectivity.

What constitutes contrasting subjectivity?

1) With other people, subjective contrast manifests when I and another subjectivity, share an experience and respond differently to it. In response, I act and speak in one way, the other acts and speaks another way. It is clear that we are encountering something analogous, but also different in important ways. What is comparable we take for objective, what contrasts we take for subjective.

2) Something similar goes on in how we account for changes to our own subjectivity. We encounter some object or situation that we have identified as identical, but at different times, and we have a different response. We act differently and we find ourselves saying different things about it. Again, what is comparable we take for objective, what contrasts we take for subjective.

My question is whether these two experiences don’t inter-illuminate. Would the subjective experience of others mean something different if we had no experience of individual subjective change, for instance if we had no mood shifts or we somehow failed to notice them? And if we were unaware of other subjective responses (for reasons of psychological impairment, or lack of interest or mistrust) would our own subjective changes have the same meaning? As I ask this, I find myself answering affirmatively: the inter-illumination, the parallax, the dialogue between intersubjectivity and change in subjectivity point to the essence of subjectivity.

…

But now look what we are doing here, right now. I am talking to you about my own experiences of comparing and contrasting my subjectivity intersubjectively and temporally – you who have had similar experiences, or maybe your experiences have differed in some way. Look at us comparing and contrasting our experiences of comparing and contrasting comparisons and contrasts…

The form is self-similar: dialogue within dialogue within dialogue. Dialogue, “with-logos”.

*

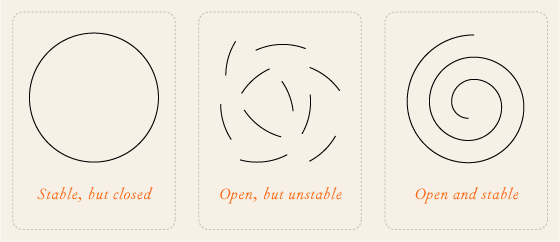

We know other subjectivities through dialogue, because dialogue directly changes one’s own subjectivity, and that change is manifested by the 10,000 things of the world. Dialogue is direct intersubjective encounter, mediated by the world. Synesis – the Greek word for understanding (literally “togetherness”) – is seeing the togetherness of the world together. Synesis is in the parallax between your eyes, the stereophonicity between your ears, in the objectifying that arises in the between-ness of your senses, between the voices conversing in your head about objects and experiences, spoken in your native language and in images and raw analogies. This complex, changing dynamically stable togetherness, which each of us abbreviates as self, and calls “I” or “me”, speaks to other selves and interacts with them as if they were simple, and often as if they were objects. Sometimes the self mistakes itself for an object, something that is primarily a thing or an image. It is hard to know one’s self.

*

According to the book of Genesis, on the sixth day, after creating our world, speaking it into existence:

God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.” So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.

The book of John describes it differently, but compatibly:

In the beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men.

*

Many people think of the universe as physical. A person is a physical being somehow invested with subjectivity. Subjectivity is inexplicable, and explained through our most mysterious physical forces.

Many others think of the universe as spiritual. A person is a spiritual being somehow in the midst of a world we take for physical. Of these, some think of the individual as the ultimate subjective unit. Others think of their nation or religion or church or race or party as the ultimate subjective unit. These perspectives are solipsistic, the former is a solipsistic individual, the latter is a solipsistic collective.

Others think of the universe as spiritual, but that subjective being is elastic and variable and conducted by communication.