Since the early 20th Century, much has been made of the role language plays in understanding. As a designer, I am tempted to say too much has been made of it.

In human-centered design we are accustomed to seeing people do things apparently unthinkingly, gropingly, experimentally — but then afterwards, when we ask for an account of the actions, we’ll get an explanation that clearly conflicts with what we observed. When I read about split brain experiments in Jonathan Haidt’s Happiness Hypothesis, which showed how the rational part of the brain confabulates explanations of parts of its own organ to which it has no access, it all rang familiar. Usability tests are full of obvious confabulations, and this is why we observe behaviors in addition to doing contextual interviews.

Designers quickly learn that users’ mouths are not fully qualified to speak for their own hands. But increasing I am doubting if users’ mouths are fully qualified to speak for their own mouths.

This spreading suspicion is derived from one important characteristic of well-designed things, especially well-designed tools: they extend the being of the person who uses them. A well-designed tool merges into a user’s body and mind and disappears. A poorly designed tool refuses to merge and remains painfully and conspicuously separate from oneself. Tools, even the best-designed ones, must be learned before they merge and vanish. Once the merging and vanishing happens, the tool is known.

This tool relationship was famously described by Martin Heidegger in Being and Time. He used the example of a hammer. The normal, everyday attitude the user of the hammer has toward the hammer Heidegger called “ready-to-hand”. The hammer belongs to the equipment in the workshop and is invisibly available and used by its owner in his work activity. This is in contrast to “present-at-hand”: the mode of being where an tool is perceived as an object. Despite the standpoint most of us assume when we sit in a chair thinking about objects, present-at-hand is an exception to the rule. It normally happens only when something goes wrong and the hammer’s availability or functioning is interrupted, rendering the hammer conspicuously broken or absent, or when the tool is new and unfamiliar and is not yet mastered.

As a designer, I must also point out that a tool will frequently revert back to present-at-hand if it is badly designed and constantly demands attention due to usability snags or malfunctions. And now, 90 years after Being and Time, there is an entirely new situation that disrupts the ready-to-hand relationship. Currently our workshops are largely virtual and are equipped with software tools which are frequently updated and improved. With each improvement our tools become unfamiliar and are knocked back to present-at-hand until we can figure out how it works and practice using it, and re-master it so that it can merge back to ready-to-hand.

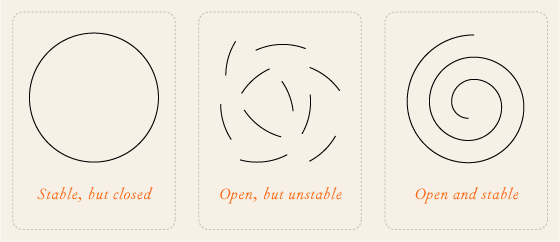

I find I have precisely this same relationship with concepts and with words. New concepts start out as present-at-hand, and they must be learned and practiced and mastered before they stop being logically connected bundles of words, become ready-to-hand (ready-to-mind) concepts which can be used for making sense of other words, arguments, objects and situations. A well-designed philosophy book guides a reader through this process, so that by the time the book concludes, a new conceptual tool has become familiar and has merged with — and, ideally disappeared into — the repertoire of concepts that makes up one’s worldview. Ideally, these concepts merge so fully into one’s own being that they become second-natural, and seem as if they are part of reality itself when we observe it.

The view that concepts and words are essentially tools (as opposed to representational models of the world) belongs to the pragmatism school of philosophy, and is called “instrumentalism”. It is a radically different way to conceptualize truth, and it changes absolutely everything once the concept is mastered becomes ready-to-mind.

There is something to be gained by refracting the pragmatic implications of instrumentalism through the theoretical insights of Heidegger’s tool phenomenology and then examining the result with the trained sensibility of the human-centered designer. My friend Jokin taught me a Basque saying: “What has a name is real.” To lend some reality to this synthesis, let’s call it “design instrumentalism”.

A design instrumentalist says “Ok. If concepts are tools, let’s design them well, so that they do what we need them to do, without malfunctioning and as life-enhancingly as possible. And let’s get clear enough on the intended purpose, users and use-contexts of each concept so that we are making smart tradeoffs and not overburdening the concept with out-of-scope requirements that undermine its design.” In other words, let’s construct concepts that produce truths that work toward the kinds of lives we want.

*

Design instrumentalism has some surprising and consequential implications.

One of them these implications concerns what it means to know. Normally, if we want to assess someone’s knowledge we request an explanation. If a lucid explanation is given, we conclude that this person “knows what they’re doing.” But is this true?

What if an ability to speak clearly about a concept is one ability, and the ability to use the concept in a practical application is a separate ability? The requirement to explicitly verbalize what one knows — as opposed to simply demonstrate mastery — might create conditions where those with linguistic felicity might appear more generally competent in everything, and those who are most able, because their ability is tacit, might find themselves under-rated and constantly burdened with false tests of their competence.

Another is an expectation that a competent practitioner can always — and should always — be able to provide a clear plan of action and a lucid justification for whatever they are setting out to accomplish. However, this is a separate skill, and not even one that precedes my ability to use the concept. This does not mean that we do not use words to assist our learning, because we certainly do rely on words as tools to help us learn. But these verbal learning tools should not be confused with the object of the learning or the substance of what is learned. They are scaffolding, not the building blocks of the edifice.

And like Heidegger’s famous hammer, which is invisibly ready-to-hand until it malfunctions, at which point it shifts into conspicuous presence-at-hand as the user inspects it to diagnose what’s wrong with it, concepts we are use are rarely verbalized while we use them for thinking. It’s only when concepts fail to invisibly and wordlessly function that we notice them and start using words as workarounds or diagnostic and repair tools for the malfunctioning concepts that are breaking our understandings.

A requirement to verbalize concepts before we use them, or while we are using them amounts to a form of multitasking.

must shift between wordlessly doing and translate the doing into words, and the two tasks interfere with one another, producing a stilted performance. Having to verbalize what we do while doing it is like embroidering while wearing thick gloves.

So, where am I going with this line of thought? The notion that all real understanding is linguistic is not only inaccurate but practically disastrous. My experience designing and experimentally evaluating designs has shown me that real understanding is, in fact, a matter of ontological extension — precisely the overcoming of language in formation of direct non-verbal interaction with some real entity. That is, unless the understanding in question is understanding how to verbalize some idea. Of course, nearly all academic work consists precisely of acquiring abilities to verbalize, so it is hardly surprising a theory that insists that all understanding is essentially linguistic would gain prominence among participants in the academic form of life.

Interposing words

Perplexity craft

Concept craft