A.

Long ago, (perhaps informed by experiences sitting in meditation?) even before I began intensive philosophical study, I adopted a psychology of “subpersonalities“. I’ve talked about it dozens of ways, but the language orbits a single conviction: our personal subjects are microcosmic societies, composed of semi-independent intuitive units.

One of the main reasons I came to this belief was noticing that subjects do not always respect the borders of the individual. Pairs of people can form a sort of personality together, and this personality can leave bits of each person behind. Sometimes this new joint-personality can threaten existing ones, leading to jealousy and estrangement.

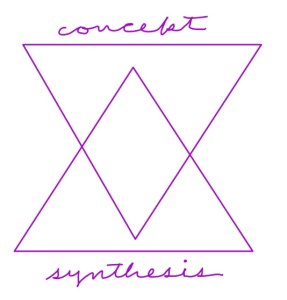

Taking-together the idea of subpersonalities and superpersonalities (“ubermenschen” wouldn’t be a bad German synonym) leaves our ordinary personal subjects in a strange position. We both comprehend subjects that are aspects of our selves, but we also are comprehended by subjects in whom we participate.

One of my most desperate insights — which I need to find a way to say clearly and persuasively — is that we are much better at thinking about what we comprehend as objects than we are at thinking what comprehends us as subjects in which we participate, but which transcend our comprehension. I believe we need to learn this participatory mode transcendent subjective thought so we can navigate difficult interpersonal and social situations we find ourselves in, and avoid the mistake (the deepest kind of category mistake) of translating these situations (literally “that in which we are situated”) into objectively comprehensible terms that make understanding impossible. We lack the enworldment to think or respond to such situations.

A subject can be smaller than, larger than, or the same size as a personal subject.

Subjectivity is scalar.

B.

Perplexity is another idea that has obsessed me since I underwent, navigated and overcame my own first perplexity, and experienced a deep and powerful epiphany — an epiphany about perplexities.

(To summarize: A perplexity is a subjective condition where our conceptions fail, and we cannot even conceive the problem, much less progress toward a solution. We instinctively fear and avoid perplexities, sensing them with feelings of apprehension at what resists comprehension, because perplexity is the dissolution of a subject.)

Emerging on the other side of my first overcome perplexity, I understood the positive, creative potential of perplexity. I realized (in the sense that it became real to me) that much of the worst pain and most egregious offense I’d sustained to that point in my life were, at least in part, perplexities that I had interpreted as externally inflicted — and that I had interpreted them that way because my objectivizing enworldment supported no other way of conceiving them.

This epiphany re-enworlded me in a way that I could discern when — or at least try to discern when — perplexities were contributing or amplifying distress in my life. When I later learned the word “metanoia” I recognized it as describing what happened to me. It happens to many people, and once you know it, you can feel it radiating from them. It is palpable.

This insight into the relationship between perplexity and epiphany is my philosopher’s stone, who transmutes leaden angst into golden insight.

The worst things that can happen to us can potentially be the best things that happen to us… if we have a sense of how to move about in the shadowy realms, where we say “here I don’t know my way about“.

Perplexity is the dissolution of subject — a sort of subjective death — that makes possible resolution of a new subject — a subjective rebirth: metanoia.

C.

If we believe that subjects can be larger than an individual subjectivity (so, for instance a marriage is a subject within which each spouse’s subject subsists)…

…and we also believe that when a subject undergoes perplexity that very deep conceptions lose their effectiveness and must be reconceived if the subject is to regain living wholeness…

…why would we suppose that only an individual person can be perplexed?

I believe that multipersonal perplexities are real.

It seems improbable that I never took-together scalar subjectivity and perplexity as the dissolution of subject, and never followed the pragmatic consequences of conceiving these ideas together, but doing so feels like… an epiphany.

*

Just as a perplexity can grip a single personal subject, it can also grip a subject of two people, or three, or a dozen or multiple dozens. It can grip hundreds, thousands, millions, or multiple billions. Entire cultures can be perplexed.

Try to imagine a perplexed marriage; a perplexed friendship; a perplexed organization, a perplexed community; a perplexed academic subject.

(Thomas Kuhn imagined perplexed scientific communities.

Try to imagine a perplexed civilization.

*

I mean “to to imagine” literally. Consider pausing and concretely trying to imagine what multipersonal perplexities might be like if encountered in real life.

Try to imagine a perplexed married couple.

Try to imagine a perplexed organization.

Try to imagine a perplexed community.

*

*

*

If you tried to imagine these scenarios, reflect: Did you imagine being in the situation as a first-person participant, subjectively experiencing the perplexity from the inside? Or did you observe the situation from outside, as an third-person observer of other people embroiled in perplexity?

Can you evert the perspective, and imagine the same scenario, situated within it as an a first-person participant, and and situated outside it as a third-person observer?

*

*

*

If you can, assume with me for a moment that collective perplexities really are possible, and consider a speculative scenario:

Party A and Party B have entered a collective perplexity.

Party A is the privileged party in these scenarios, blessed by me (the inventor of these scenarios and all the assumptions governing them) with true insights into “what is really going on”. It’s an invented scenario, so there can be a true truth here, if nowhere else.

Party B sees things differently (and, again, because this is my custom-made vanity scenario) incorrectly. Party B rejects the notion of perplexity and sees what is happening according to its own worldview, which has no perplexity concept. What Party A claims is perplexity, Party B perceives as needless conflict caused largely by Party A’s iffy (or worse) beliefs and actions.

So, Party A conceives what is happening as a collective perplexity, and attempts to engage Party B in a perplexity-resolving response — a transcendent sublation.

Consider a first variant of the scenario: Faction B wants to recover the collective mode of being that existed prior to the perplexity, and “turns around” and attempts to move back to how things were before the conflict began. How does this play out?

Now, consider a second variant: Faction B decides to bring an end to the conflict through breaking free of Faction B altogether. It secedes, or splits off, forms a new denomination, or resigns, or hits unfollow, or blocks or mutes, or divorces, or cuts off contact, or whatever separation mechanism makes sense for the kind of faction A and B are. How does this play out?

Now consider a third variant: Faction B decides to fight and dominate Faction B. It makes Faction A a deal it can’t refuse. Or it tries to use the justice to force its will. Or it tries to steal an election through various kinds of deceit and treachery. It tries to weaken, dissolve or destroy some institutions and strengthen, reinforce or build others in order to dominate faction A. How does this play out?

There is a fourth variant, but I don’t want to digress.

What is the ethical obligation of Party A and Party B in each of these variants? How does each see the other’s?

*

I have been in deeply perplexed relationships where I was the only one who saw a perplexity, and so I could not win the cooperation required to resolve it. I could not resolve the perplexity of the relationship alone, so I had to resolve the perplexity in myself. This resolved perplexity, however, is not the shared perplexity. The shared perplexity is left unresolved, unasked and unanswered in a state of nothingness.

Over the years, I have gradually learned to avoid such perplexities, except where I sense a possibility of fruitful struggle. Most of the time, with most people, however, I keep things light and gloss over anything that might cause apprehension. I have learned to get along with most people most of the time, and that means keeping my active philosophy to myself.

I have also been in many superficially perplexed relationships, which, because they were superficial, could be collaboratively resolved. Design research has been my laboratory.

Once every decade or so, I get stuck in a situation — usually with a client with little hands-on design experience, but with much learned-about “design expertise” — who can neither cooperate nor resist the impulse to dominate the process, who makes resolution of the perplexity possible. And these leave me detaching from the shared perplexity and resolving a perplexity of my own, not the shared one.

(I feel every lost shared perplexity, whether deep or shallow, like an intellectual phantom limb. It is nothing — but nothingness feels terrible. I see no reason to pretend it doesn’t bother me, or that I can just unilaterally “forgive”, which an individual effort, without mutual reconciliation, which is a collaborative effort.)

I have also had one extremely deep shared perplexity resolve in a shared resolution.

“Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes”

That was the deep uncanny mine of souls.

Like veins of silver ore, they silently

moved through its massive darkness. Blood welled up

among the roots, on its way to the world of men,

and in the dark it looked as hard as stone.

Nothing else was red.

There were cliffs there,

and forests made of mist. There were bridges

spanning the void, and that great gray blind lake

which hung above its distant bottom

like the sky on a rainy day above a landscape.

And through the gentle, unresisting meadows

one pale path unrolled like a strip of cotton.

Down this path they were coming.

In front, the slender man in the blue cloak —

mute, impatient, looking straight ahead.

In large, greedy, unchewed bites his walk

devoured the path; his hands hung at his sides,

tight and heavy, out of the failing folds,

no longer conscious of the delicate lyre

which had grown into his left arm, like a slip

of roses grafted onto an olive tree.

His senses felt as though they were split in two:

his sight would race ahead of him like a dog,

stop, come back, then rushing off again

would stand, impatient, at the path’s next turn, —

but his hearing, like an odor, stayed behind.

Sometimes it seemed to him as though it reached

back to the footsteps of those other two

who were to follow him, up the long path home.

But then, once more, it was just his own steps’ echo,

or the wind inside his cloak, that made the sound.

He said to himself, they had to be behind him;

said it aloud and heard it fade away.

They had to be behind him, but their steps

were ominously soft. If only he could

turn around, just once (but looking back

would ruin this entire work, so near

completion), then he could not fail to see them,

those other two, who followed him so softly:

The god of speed and distant messages,

a traveler’s hood above his shining eyes,

his slender staff held out in front of him,

and little wings fluttering at his ankles;

and on his left arm, barely touching it: she.

A woman so loved that from one lyre there came

more lament than from all lamenting women;

that a whole world of lament arose, in which

all nature reappeared: forest and valley,

road and village, field and stream and animal;

and that around this lament-world, even as

around the other earth, a sun revolved

and a silent star-filled heaven, a lament-

heaven, with its own, disfigured stars –:

So greatly was she loved.

But now she walked beside the graceful god,

her steps constricted by the trailing graveclothes,

uncertain, gentle, and without impatience.

She was deep within herself, like a woman heavy

with child, and did not see the man in front

or the path ascending steeply into life.

Deep within herself. Being dead

filled her beyond fulfillment. Like a fruit

suffused with its own mystery and sweetness,

she was filled with her vast death, which was so new,

she could not understand that it had happened.

She had come into a new virginity

and was untouchable; her sex had closed

like a young flower at nightfall, and her hands

had grown so unused to marriage that the god’s

infinitely gentle touch of guidance

hurt her, like an undesired kiss.

She was no longer that woman with blue eyes

who once had echoed through the poet’s songs,

no longer the wide couch’s scent and island,

and that man’s property no longer.

She was already loosened like long hair,

poured out like fallen rain,

shared like a limitless supply.

She was already root.

And when, abruptly,

the god put out his hand to stop her, saying,

with sorrow in his voice: He has turned around –,

she could not understand, and softly answered

Who?

Far away,

dark before the shining exit-gates,

someone or other stood, whose features were

unrecognizable. He stood and saw

how, on the strip of road among the meadows,

with a mournful look, the god of messages

silently turned to follow the small figure

already walking back along the path,

her steps constricted by the trailing graveclothes,

uncertain, gentle, and without impatience.

— Rainer Maria Rilke