I’ve written quite a bit on what I view as the twins roots of moral inadequacy, hubris (closedness to being beyond the self, and akrasia (lacking any enduring continuity of self, often translated “moral incontinence”).

I’ve also written about the fact that the being of an individual and the being of a collectivity are not as dissimilar as we think. The dynamic that allows an individual achieve spiritual integrity is the same as that which helps a group accomplish the same thing. We are whole as individuals — that is, we have a stable soul — by virtue of inner dialogue. Without dialogue we’re a tangle of conflicting spiritual impulses, writhing, biting and crushing one another in the effort to dominate the entire self.

Dialogue is the practice of teaching and learning that allows the various impulses/instincts/spirits within us to communicate, harmonize and work together toward an order universally experienced as good.

*

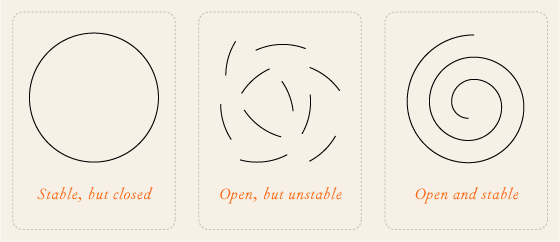

Here is a visualization of hubris, akrasia and dialogue:

*

We are sane because we talk to ourselves — and recognize that it is our own self with whom we talk.

This is true for each of us (as individuals), and it is true for all of us (as communities).

*

“Madness is rare in individuals – but in groups, parties, nations, and ages it is the rule.”

*

Human beings have learned to integrate their individual selves in such a way that they are neither hubristically closed, nor akratically unstable, but both stable and open like a spiral. Collectivities of people have not learned this art, and still fail to recognize the obligation to be moral like we expect individuals to be.

Instead we find either the oppressive, closed stability of authoritarian organizations, or we find nebulous, “free” and reactionary organizations that change their story with every change in circumstance.

My belief is that organizations must learn to avoid hubris and akrasia, and and earn the right to loyalty — just as every individual must, if he wishes to have lasting friendships or a functioning marriage.

It is impossible to be friends with someone who is hubristic because you do not exist to him as a fellow-subject. To such a person you are a thing with a use. But we have no problem forming relationships with hubristic organizations. In fact we sort of expect organizational hubris. Is it wise to commit ourselves to an organization that doesn’t recognize us as subjects who participate in its being, but instead regards us as objects to utilize for its own purposes?

It is equally impossible to be friends with someone who is akratic, because that person is a different person in every situation. There’s no enduring other to be friends with. There’s a different story every day, and her role, your role, and your relationship shape-shifts to fit the new narrative. But we act like organizations have a right to be akratic — it’s just “responding to conditions.” Is it wise to found our lives on an organization that doesn’t acknowledge any responsibility to serve as a steady foundation, but who arbitrarily changes the terms of the relationship based on mood and circumstance whenever it seems convenient?

It’s a quite a shift to view organizations in terms of human being (v.) — to believe in corporate personhood — but once you make that shift, the moral double-standard is conspicuous. Organizations behave in ways we would never accept from an individual, because we sort of expect it.

*

If we wish to have community we must revaluate our ethics. We must demand certain ethical standards from our organizations — from our selves, to our marriages, to our friendships, to our social circle, to our businesses to our governments — and this means we must also hold ourselves responsible as agents of organizations. We cannot constantly shift roles, one minute a representative of an organization, and the next minute an individual who cannot answer for his organization’s behavior.

We need language for an ethic that does justice to the insights of social psychology. Most people are dispositionalists — behavioristic atomists who assume that the behavior of a groups is determined by the individuals that constitute it — not because they’ve given the matter any thought, but because they’ve never noticed they’ve adopted dispositionalism as an assumption. We barely even notice the interpretive violence we do in force-fitting social phenomena into individualistic psychologies and moralities.

*

What is great about capitalism is that we are all empowered to establish our own little states, each its own ethos and ethic. We can experiment and see where things go in practice, without danger of violence. Every company is a little political laboratory.

One thought on “Revaluating the work ethic”